When Nigerians talk about founding fathers, they refer to Ahmadu Bello (Sardauna), Nnamdi Azikiwe and Obafemi Awolowo. Whereas modern Nigeria existed before these three were born.

The first time Bello arrived on the national scene was in 1947 after the new 1946 Arthur Richards Constitution amalgamated the North and South legislative assemblies. He led the northern legislators to Lagos, the seat of the national legislature.

Awolowo became known nationwide on 7 January 1937 when, as Organising Secretary of the Motor Transport Union, he organised a motor transport strike to protest the increase in tariff which the government imposed since the lorries were taking business away from the railway. The government had incurred a huge debt in building the railways.

They counted on increased patronage to service the debts. But in the Western Region, lorry haulage proved a cheaper alternative so the government imposed tariff to force commerce back to the railway. Awolowo called out the pickets, which lasted for six days and held Lagos, the nation’s capital, to a standstill.

Azikiwe captured the nation’s attention when, in 1937, he arrived Nigeria with an electrifying personality, a bundle of talents and on 22 November 1937 he published the maiden edition of his popular newspaper, The West African Pilot.

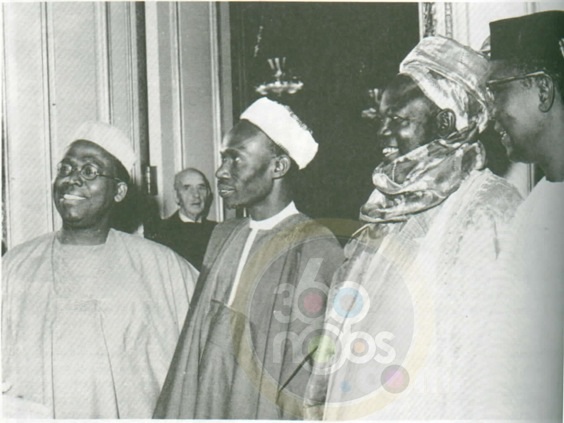

The first time all the three met together was on Friday, 19 June 1953. Enahoro’s Self-Government-Now bill and the consequent resignation of all Action Group’s federal ministers caused a constitutional crisis which made Nigeria ungovernable.

Oliver Lyttleton, the secretary of state for colonies, tried to salvage the situation by inviting the main players to a constitutional conference in London. But Awolowo and Azikiwe, who had become friends since Enahoro’s bill was tabled, refused the terms and conditions. Sardauna was fine with them. And so Macpherson, Nigeria’s governor, brought Sardauna, Azikiwe and Awolowo together in his office to jointly fashion new terms and conditions.

After the meeting which ended 10:10pm, he presented the trio to the media and Daily Times the following day named them The Big Three. Since then it stuck that they were founding fathers because their tribes and their parties were the largest and because it offered an inclusive impression that all the regions had a say in the formation of the country.

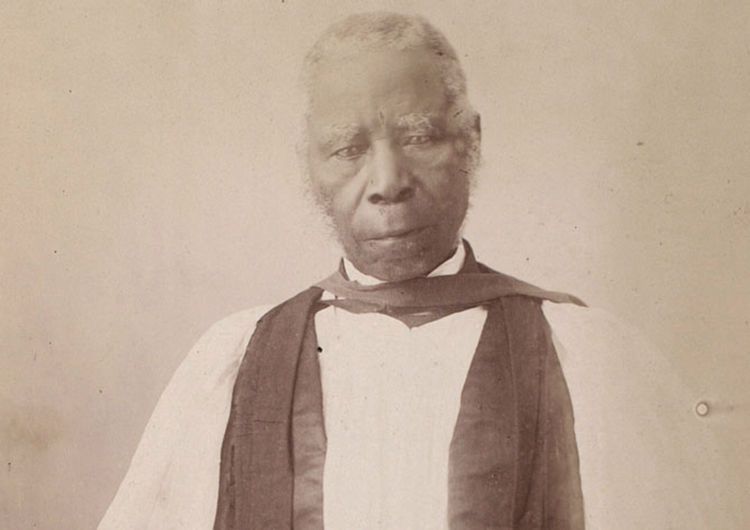

This is far from the truth. Modern Nigeria started at Windsor Castle, on 23 November 1851, when Ajayi Crowther, the first of Nigeria’s founding fathers, surveyed West Africa with Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert and said Lagos must be bombed.

On 7 April 1822, when the 13-year-old Samuel Ajayi Crowther was rescued from the belly of a slave ship heading for America, he thought all was finished. A year before, around breakfast, together with his mother and sister he was captured by Fulani slave raiders when they attacked his village of Osogun, 140km inland of Lagos coast.

He wrote in his autobiography: “Men and boys were at first chained together, with a chain of about six fathoms in length, thrust through an iron fetter on the neck of every individual, and fastened at both ends with padlocks.” Later, the little Crowther’s chains and padlocks were removed to his relief, only to be yanked from his family and exchanged for a horse.

Crowther fell sick and attempted suicide when he heard that his new owner planned to reap huge profits out of him by taking him south-westward to Little Popo, a flourishing high-paying Portuguese slave market (a major outlet for slaves from the Oyo Empire now known as Aného in Togo).

The owner feared that the little boy’s suicide bid may succeed before the next slave auction so she quickly exchanged him for a bottle of English wine and some tobacco leaves. The Ijebu man who bought him took him south-eastward to Lagos and sold him to the Portuguese slave ship Esperenza Feliz, meaning Free Spirit.

As he lay chained from the neck to the deck, he thought of his father killed during the Fulani invasion of their village, he thought of his mother and sisters whom he would never see again. He thought of how he was exchanged for a horse, wine and tobacco leaves. He despaired and awaited death as the ship sailed towards America.

Then HMS Myrmidon, captained by Sir Henry Leeke of the Royal Navy’s anti-slavery squadron, engaged the Portuguese slave vessel in a gunfight. Crowther and some other slaves were rescued and taken to the British settlement in Freetown (now in Sierra Leone).

The Church Missionary Society managing the settlement taught him to read and write, enrolled him in Fourah Bay College and sent him to England to study. He spoke Latin, Greek and Hebrew and many West African languages.

Being a fascinating personality, highly educated black man, an ex-slave and an inveterate writer, his public lectures all over Britain drew crowds. He later bagged an honorary doctorate degree at Oxford University.

In Canterbury Cathedral on 29 June 1864 when Ajayi Crowther became the first black Bishop ordained into the Anglican Church, Sir Henry Leeke, the captain of the ship that rescued him from slavery in 1822, came over to witness the event. Lady Weeks who taught him the ABC alphabets was also there. It was a tearful reunion.

The highest honour given a visiting dignitary in England was to be asked to meet the Queen. On 18 November 1851, Crowther, accompanied by Lord Russell, was invited to the Windsor Castle.

While waiting in the grand crimson drawing room, a lady gorgeously attired with a long train gracefully stepped in and without being prompted, Crowther paid her all the obeisance he could as he had been coached to address Her Majesty.

When the lady left, he was told she was one of ladies-in-waiting, not Her Majesty. He said, “If the lady-in-waiting is so superbly dressed what would be that of the Queen herself?”

Then he was called into another ornately furnished room where he met Prince Albert, husband to the Queen, and they started discussing how he was enslaved and the general situation of slavery in Lagos.

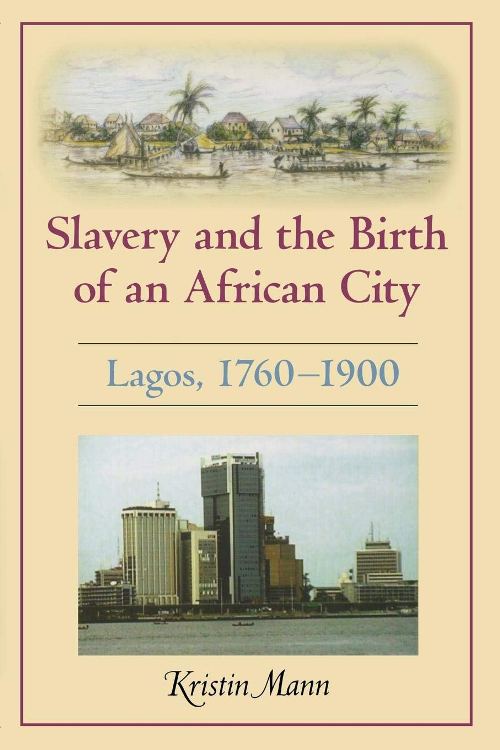

According to Professor Kristin Mann’s unsung scholarly tour de force, Slavery and the Birth of an African City: Lagos, 1760–1900, the first recorded overseas slave export from Lagos was in 1652 aboard the English ship, Constant Ruth. She purchased 216 slaves and sailed them to Barbados to start a barbaric life, leaving a barbaric trend behind.

As Crowther spoke to the Prince, export of slaves from Lagos peaked at 37,715 for 1851. That was not counting several slaves like Crowther’s mother and sisters who were used locally or beheaded for religious celebrations. Not to own a slave was an indication that you were poor.

When the late Prince Odiri, the son of Akazua, the Obi of Onitsha was to be buried in September 1864, some slaves were buried with the corpse; among them was an eight-year-old girl who carried a pair of shoes and foodstuff to serve as refreshment for the late prince on the long journey to the great beyond.

Crowther and his fellow missionaries tried to offer money to free the slaves but Akazua said no; the tradition of the land must be respected.

In Ibadan, the war-crazed city, when the Balogun (War General) passed away, 70 slaves’ blood was drenched over his grave as a mark of honour to his accomplishments.

Efunsetan Aniwura, the Iyalode of Ibadan, had several farms and households full of slaves. She made it an abomination for slaves to love or to make love. When one of her slaves became visibly pregnant, she marched her to the Ibadan town square and beheaded her there herself.

The celebrated Madam Tinubu, Efunsetan’s dear friend and business partner, was also a slave dealer who owned an Ibadan-to-Lagos pipeline delivering slaves for Brazilian and Portuguese export. Her husband, Oba Adele, and the Lagos kings before and after him, were slave magnates who owned warehouses for processing or hoarding slaves to maximise their market value.

As Slavery and the Birth of an African City correctly states, slaves sold from the king’s warehouse, farm or household usually commanded higher fees than other slaves. These kings also set up aggressive enforcements to lock down their own lucrative commissions from all slave deals.

Prince Kosoko, who was Oba Eshinlokun’s son, did not wait to be king before becoming a major slave trader. Princess Opo Olu, Kosoko’s sister, owned 1,400 slaves. Oshodi Tapa, Dada Antonio and Ojo Akanbi, like Ajayi Crowther, were former slaves but unlike Crowther rose to become slave merchants themselves.

Of all Lagos Obas since Asipa and Ado, Akinsemoyin, Ologun Kutere, Eshinlokun, Akitoye and Kosoko were the biggest slave traders, sending their fellow Africans to the Americas more than any monarch.

By 1840, the population of Lagos had swollen dramatically and half of them were either domestic slaves or slaves being processed for export. The females were usually domestic slaves while the males were processed for export. That was why Crowther was separated from his mother and sisters and transferred to a different market.

And the revenue from slave trade streamed in steadily. The 25 guns lining Lagos Island to the King’s palace were purchased with slaves’ money. Velvet clothes, royal umbrellas, hats and stylish robes worn by the Obas and chiefs to command respect and admiration amongst their people were bought with slaves’ money.

In fact, Oba Kosoko did what others never did. He bought back slaves already established in Bahia, Brazil because he needed their carpentry, masonry and coopering skills to build Brazilian-type houses and produce European items in Lagos.

Meanwhile, as Crowther spoke about the horrors of slavery, a lady minimally dressed and too unassuming to deserve interruption of the narration came in and she listened to him with breathless attention.

There was no voice speaking for the slaves in West Africa until the British rescued Crowther, gave him dignity, gave him culture and education and he became a voice; the voice.

And when the Prince spread the map on the table wider to see Lagos, it blew out the candle light. As Crowther wrote in his autobiography, the Prince then said, “Will your Majesty kindly bring us a candle from the mantelpiece?”

Then it dawned on Crowther the unassuming woman who had joined them earlier on was Victoria, Queen of the United Kingdom and Empress of India. Wrote Crowther: “On hearing this, I became aware of the person before whom I was all of the time. I trembled from head to foot, and could not open my mouth to answer the questions that followed. Lord Russell and the Prince told me not to be frightened, and the smiles on the face of the good Queen assured me that she was not angry at the liberty I took in speaking so freely before her, and so my fears subsided.”

After bringing the candles, the Queen then asked about what she could do about the slave situation in Lagos, Ajayi Crowther said seize Lagos by fire by force.

Captain Labulo Davies, the second of the founding fathers, was a lieutenant on HMS Bloodhound, the flagship of the fleet that bombed Lagos.

The belief in fate always set a limit on one’s achievements. What set the founding fathers apart was the shared recognition of moral deficiency in their fellow Africans which made the inflicted cruelties of slavery possible.

The founding fathers did not believe that it was the fate of slaves to be slaves and the fate of others to get them chained or be led to the waiting ships; they did not believe that that was how the world was made and there was no reason to change it.

They had regard for the humanity of slaves; they had empathy for their sufferings. Slavery was simply man’s deliberate inhumanity to fellow man.

Crowther and his future wife, Asano, met on the same British ship heading to Freetown after his rescue. He was being rescued for the first time, she the second time.

The British started the policy of relocating slaves to the missionary-administered Freetown because earlier on when the slaves were handed over to Oba Adele, Eshinlokun, Ghezo or any other monarchies along the coasts of Bight of Benin, they were resold into slavery once the British sailors got back to their ships.

And so British policy shifted to relocation of rescued slaves to Freetown. The settlement proved so successful (boasting the first secondary school, the only tertiary intuition in West Africa, high income from agricultural trade with the British Empire) that when Crowther asked the Queen to bomb Lagos and persuade King Dosumu to relinquish control in 1861, he had Freetown in mind as the model for development.

Sparks flew, the heavens rocked, one thing led to the other, from slave and slave, Ajayi and Asano became man and wife in Freetown. They, their children, their children’s children dedicated themselves to stopping slavery and promoting the principles of civilisation.

In August 2014, the family continued the trend when their great-great-great grand daughter, Dr. Ameyo Adadevoh, gave her life to save Nigeria from the spread of Ebola.

According to Elebute and Mann, the Crowthers and Davies were the two families which the Royal Navy were given standing order to rescue should there be an eruption of violence and British subjects had to be evacuated.

It mattered less if several British servicemen were lost in tracking these Africans down. They must be rescued. And in fact when Crowther was kidnapped for 10 days by Abboko at Idah in 1868, Mr. Fell, the British vice-consul at Lokoja, was shot dead with a poisoned arrow after he led the squad to forcefully rescue Crowther when Crowther insisted that no ransom should be paid on him.

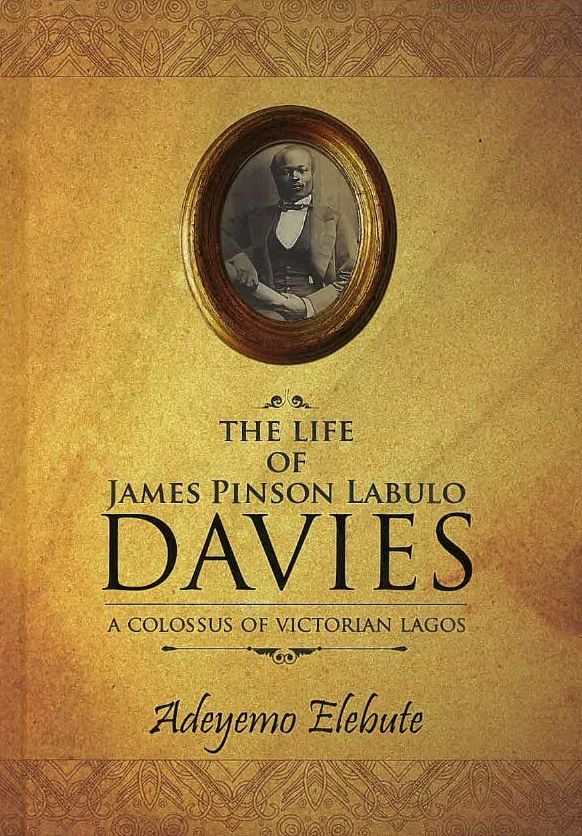

The life of Captain Labulo Davies was too compelling, too needed and too unknown that Adeyemo Elebute, a professor of surgery for 45 years and a foundation staff member of Lagos University College Hospital (LUTH), turned himself into a professional historian at 82 years of age. He travelled far and wide, burrowed into many Nigerian and British archives in order to lock down Davies’ story in this splendid book.

Davies was born on 14 August 1828 to former Yoruba slaves whom the British had rescued and resettled in Freetown. His father was from Abeokuta and his mother from Ogbomoso. His parents refused to accept that Africans should be left to their traditions and ways of life after what they had done to them. Their son joined the Royal Navy as a sea cadet in 1849 and later, when he retired began his own shipping line. Being trustworthy, he became a point of contact for many European trading companies in West Africa. He grew rich.

If CMS was the first secondary school in Nigeria that produced some of the greatest Nigerian minds of last century, it was because Captain Davies funded this initiative of Thomas Babington Macaulay (Ajayi Crowther’s son-in-law and Herbert Macaulay’s father).

If the Western Region’s premier, Obafemi Awolowo, could afford to use wealth from cocoa to pay for free education, free health for all the residents of the region irrespective of tribe or class, it was because of Davies who brought the cocoa plant and the “gospel of cocoa” to the coast of West Africa, starting from his farm in Ijon village.

Intriguingly, when the April 1916 edition of Journal of African Society credited Sir Brandford Griffiths, the British governor of Gold Coast (Ghana) from 1885-1895, for introducing cocoa to West Africa, his son, W.B. Griffiths, who was then the colonial Chief Justice of the same Gold Coast, issued a rebuttal saying it wasn’t his father but their family friend “the late Capt. J.P.L. a well-known native of Lagos”.

For 30 years, Davies was the richest man on all the coast of West Africa. At a time when millions of his fellow Africans had never seen a ship before, and those that had seen them thought ships belonged to the white man, Davies owned merchant ships plying the Lokoja, Lagos, Freetown to Plymouth, Portsmouth, Brighton and Liverpool route.

When Madam Tinubu ran into financial difficulties after the new British government in Lagos banned slavery, Davies bailed her out in exchange for some of her juicy landed assets at “Tinubu Square at Oko Faji”. Davies also bought land from Alli Balogun, who, like Madame Tinubu, was an ex-slave merchant turned palm kernel and cotton merchant.

On 18 March 1872, Davies mortgaged “fourteen parcels of prime real estate” in exchange for a record-breaking credit of £60,000 a year [1.7 billion naira in today’s value] from Child Mills Company in Manchester.

This was over and beyond the record set by his rival Lagos rich man, Taiwo Olowo, who during the Kiriji War (1877-1886) supplied Ibadan with those mighty cannons that gave the war its name. To underscore the partnership between European and African businessmen immediately after the ban on slavery, on 20 February 1867 Taiwo Olowo, according to Mann, received goods and currency on credit from Regis Aine (a French trading company) sufficient to purchase 40,000 gallons of palm oil by mortgaging his 17 properties.

The stellar qualities of Davies, his achievements, his laudable effort at civilising his fellow West Africans in ways of modernity reached the Queen at Buckingham Palace. She summoned her goddaughter, Aina Sarah Forbes Bonetta, and said she should consider having Captain Davies as future husband. Aina was 17 and Captain Davies 33.

When the Kingdom of Dahomey broke away from a weakened Oyo Empire, it rose rapidly to become an important military power capturing towns and villages from the grip of Oyo Alaafin.

To get slaves, you need war. Port Novo, Whydah, Ouidah, Popo that used to be some of Oyo’s contact with Euro-Brazilian ship owners became important slave trading ports for Dahomey. With the British government becoming proactive with its anti-slavery campaign, Commander Forbes was sent in 1849 to 1850 to meet and persuade the King of Dahomey to switch to trade in cotton, palm kernel and other agriculture items as a key source of income instead of trade in slaves.

At the meeting, some slaves had been earmarked to be beheaded for religious ritual. One of them was Aina, then a seven-year-old girl who had already witnessed the killing of her parents when Gezo’s army invaded their Egbado village of Oke Odan in 1848 and took her as a slave.

Commander Forbes used everything to persuade Gezo to release the little girl to him. Gezo refused. The game changed when Forbes said: “She would be a present from the King of the Blacks to the Queen of the Whites.”

But it was not true that Queen Victoria was the queen of the whites and Gezo definitely knew he was not king of the blacks. There were his immediate superiors: Alaafin Abiodun Atiba in Oyo and Oba Osemwende and Adolo in Benin. But being a megalomaniac, by equating him with Queen Victoria, Forbes ballooned his estimate.

And Gezo saw that being the Queen’s coequal, he would earn more respect and command more power from Alaafin and Oba of Benin. He released Aina.

When Aina eventually arrived at Windsor Castle on 9 November 1850, the Queen, who never knew Commander Forbes nor asked him to bring back a black girl, adopted Aina and sent her for royal training. The girl not only impressed the Queen with her charm, intelligence and willingness to blend, she impressed the whole of Britain.

She spoke English with a royal accent unlike millions of other Britons. Several photographers, illustrators and artists came to document her. Even foreign dignitaries who came to visit the Palace saw Princess Aina with the royal family and wrote about her.

Her presence was sufficient to confound and debunk the pernicious racist theory then that blacks were of least intelligence. The phrenologist even came to measure her skull. With the royal family having a black Princess with her own waiting ladies, it was difficult to regard blacks as monkeys in respectable circles in Britain.

During the meeting with Ajayi Crowther at the Windsor Castle, the Queen asked whether Aina’s gifts were due to her noble blood. Crowther answered that she wasn’t a descendant of one of those mighty kings of West African empires or kingdoms but her parents were chiefs of a small town.

Since the Queen arranged the marriages of all her six children, she arranged Aina’s marriage too to Captain Davies, supremely confident she was in good hands. The wedding was held at St. Nicholas Church, Brighton on 14 August 1862.

The Queen paid for the elaborate ceremony which was the talk of the country. And when both settled in Lagos, they continued the course of civilisation, opening schools, educating the people and discouraging slavery.

They were the reason why there was no major uproar against British presence in Nigeria unlike in other countries like Ghana, Kenya and India. They earned the trust of fellow Africans and the colonial governments across West Africa respected them.

In fact, Michael J.C. Echeruo’s remarkable book, Victorian Lagos: Aspect of Nineteenth Century Lagos Life provided rare photographic evidence of black and white Lagosians living together, trading together and socialising together as equals.

No party organised by the governor or any elite was complete without the presence of Aina Davies. She was in regular correspondence with the Queen and the Queen sent gifts to her and invited her when there were family functions in London.

A word from Aina about cruelty of a British governor or consul would make that governor to be removed. And the governor and consuls were very careful about the impression they were giving Mrs. Davies. Nigeria would not have become a South Africa where theories of racial superiority became institutionalised.

Even Nnamdi Azikiwe’s popular West African Pilot said on Tuesday, May 23, 1939 when drumming up support for the Empire Day celebrations:

“Tomorrow is Empire Day, a day to which school children all over the British Empire look with eagerness. It is a day set apart to remind us of the unblemished deeds and acts of a queen whose memory should never be obliterated from the minds of the African.

“Her Majesty, Queen Victoria, called ‘Victoria the Good’, was responsible for many kind acts which have helped immortalise her among us. Can we forget the [Lagos] cession of 1862, the gift of a staff to the late King Akitoye, the Bible sent to Sagbuwa the Alake of the Egbas, the adoption of Bonnetta Forbes afterwards, Mrs J.P.L. Davies, and such like?”

But that was pre-war era before USSR penetrated Nigeria with Marxist viewpoint and analysis and British presence became regarded as colonisation and imperialism. But Oyo, Benin, Fulani empires were not seen as imperialism.

The liberation from slavery, the mass education by the British, the health and social services provided, the railways, the infrastructural facilities built then, became known tools of colonial exploitative expansion.

Hebert Macaulay became regarded as nationalist when in actual fact he was what is today called government critic, human rights or civil society advocate. He never called for the British government to leave Nigeria. Till the last, he swore allegiance to the British crown.

In his Justitia Fiat: the Moral Obligation of the British Government to the House of King Docemo of Lagos, he wrote with pride about the role his grandfather, Ajayi Crowther, played in asking the British to take over the political affairs of the country and modernise the place.

Also figures like Captain Labulo Davies, Henry Carr, the inspector of schools of the Colony of Lagos who favoured assimilation with White Lagosians; Otunba Payne, the chief registrar of Lagos Supreme Court in 1877 who prepared the indigenous handbook for white judges to use, became blotted out from the history books once anti-colonial discourse took firm root. And slaveholders and beheaders like Oba Ovonramwen Nogbaisi were resurrected as heroes.

Today, the slavery disempowering Nigeria is enslavement to the pastor, enslavement to the caliphate, enslavement to the Quran, enslavement to word of God, enslavement to churches and the diviners; enslavement to superstitious thinking. Yet we are not even seeing their grip on our minds as slavery. We thank Professors Adeyemo Elebute and Karen Mann for showing us how overcoming the forces of enslavement and cooperating with agents of modernisation made an icon and a city.

Damola Awoyokun is the author of the forthcoming book ‘Cantilever: History of Nigeria from 1822 – 1970’ Volumes I- III